Over the past couple of months, I have been working to make it easy for administrators to create and maintain a complex security policy for a giant archive of digital artifacts. In the process, I think I have found a useful way to configure complex software systems such as Zope 3.

A Security Policy for Dead People

The archive in question stores images, documents, and various other records about dead people. (Genealogy is mostly about dead people, after all!) The archive has not yet been deployed, but it will replace an existing simpler system. Assuming the archive is successful, developers at familysearch.org (my employer) will want to adopt it for their own purposes. As adoption grows, so will the complexity of the security policy applied to the archive. Therefore, the security policy must be manageable. People should not fear the prospect of making changes to the security policy. Changes in how the system is used should lead to changes in the policy. If the policy does not evolve with usage, the archive will stagnate to some extent and so will some of the work being done.

Because the requirements are complex, the security policy is also complex. There are currently six degrees of freedom, meaning that there are six independent variables that affect the outcome of a security policy check. I don’t know about everyone else, but my quick intuition is typically limited to three dimensions; any more requires a great deal more rational exercise. Six dimensions is often too much to work with quickly and confidently.

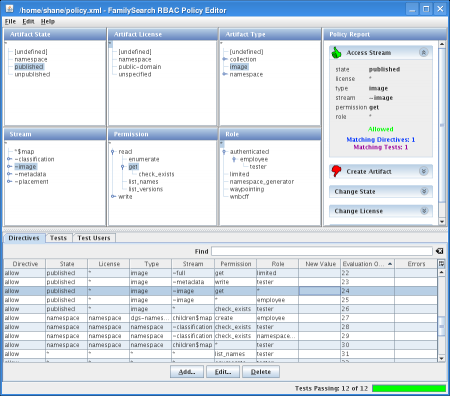

However, I believe the right user interface can optimize that kind of rational exercise. Following that belief, I created a graphical tool for managing the security policy. It can answer questions with simple interactions, increasing people’s confidence that they are changing the policy correctly. I eliminated the need for humans to parse and generate XML, which I think they will find helpful. But the best part, I think, is I put test-first methodology right before the user’s face. A screen shot follows.

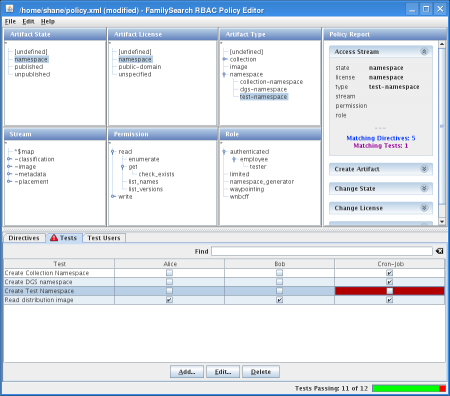

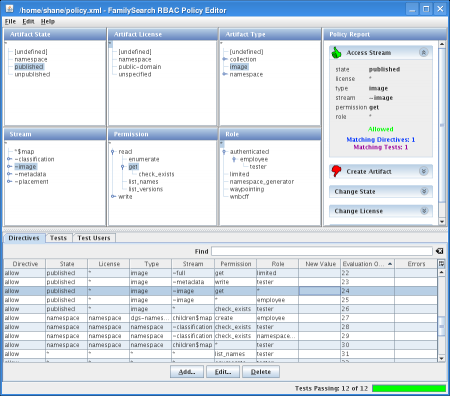

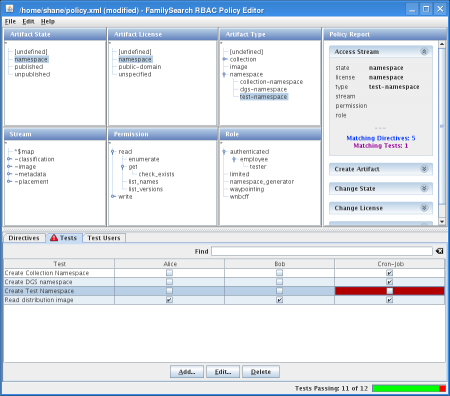

The acronym RBAC in the title stands for Role-Based Access Control. The six trees in the top left represent the six degrees of freedom; each degree has a grouping hierarchy. On the right is a report of whether users attempting the selected combination would be granted access. The reports are updated instantly whenever the user selects a tree node. The screen shot posted here is showing that according to the policy.xml file in my home directory, users with any role can retrieve any image stream of any published image artifact, regardless of license. This interface is the place to change that policy.

At the bottom, there are three tabs. The first tab has a table showing all policy directives. A directive states that access is to be allowed or denied if the request fits the specified combination. To change the policy so that people must at least be authenticated before viewing images, the user of this application simply selects the directive shown, clicks the Edit button, chooses a different role, and clicks Ok.

In the status bar is a report of how many tests are passing. If people use this feature, I expect the application to be quite successful. The tests tab contains a matrix of tests and test users; each test user has a list of roles. The cells of the matrix each have a checkbox that shows whether a given test user is expected to be able to do something according to the policy. If the outcome of the policy does not match the expectation, the cell turns red and the number of passing tests decreases.

The report panels on the right feature the ability to show all directives or tests that meet some criteria. If I want to know why someone’s access is denied when I thought some directive allowed it, I select the conditions of their request, then look on the right to see what the policy says about it. If it says no directives match, then I select or deselect conditions on the left until I find the directive that needs to change. If there really is no directive that matches, I add a new directive (and a test!) and verify the change using the report panels again.

The application has other goodies designed to increase users’ confidence, such as fully integrated undo/redo, error and warning highlights instead of cryptic dialog boxes, and “find” fields that filter the rows of the tables. I expect that this is enough for a security policy administrator. To make it as friendly as an iPod is not a goal and would even be a disservice for people who are responsible for complex things like a security policy.

A Configuration for Living People

Throughout the process of designing and implementing this, I have kept one thought in my mind: could I use something like this to configure components in the Zope component architecture? The component architecture solves big, interesting problems, but it also makes the outcome of configuration decisions much less obvious. If I made an application like this that lets you see and modify the outcome of configuration decisions interactively, would it be useful to the developer community at large?

Boy, would I love to find out. I started the Zope Jam project some time ago and haven’t done anything with it since, although I thought my initial prototypes looked promising. I stopped the project because I felt something nagging at me that the design was wrong. Now I think I see one specific blocker: the whole thing was designed around ZCML. It appears today that the Zope community strongly supports the component architecture, but not necessarily ZCML. So the new project would be an interactive configuration browser and it may support more than one way of modifying the configuration.

I still prefer to make it a desktop GUI application (written in Python, rather than Java Swing, which was required for the policy editor), with a variety of low-latency widgets and no access control issues, rather than a browser-based application. It should run user code directly, so that when the user asks what the outcome of an adapter lookup would be, the GUI’s answer would always be correct. It should integrate tests of the configuration much like I did with the policy editor. It should do everything possible to increase the software developer’s confidence in the component architecture.

Let’s Build This

Does anyone else get excited about this? I love finding ways to make complex things simple. If I could find a company to fund the development of this, I would work on it full time. I think it would be a major time saver for any company that is doing significant software development using the Zope component architecture.